In this article

PCOS: A misleading nameDiagnostic criteria: What the international guidelines say1. Hyperandrogenism2. Ovulatory dysfunction3. Polycystic ovarian morphologyDifferential diagnosis: An essential stepThe three self-reinforcing mechanismsInsulin resistance and hyperinsulinemiaChronic low-grade inflammationDysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axisThe four clinical profiles of PCOS1. Insulin resistance-dominant PCOS2. Inflammatory-dominant PCOS3. Post-contraception profile4. Adrenal-dominant PCOSThe most frequent symptomsReproductive symptomsDermatological symptoms (linked to hyperandrogenism)Metabolic symptomsPsychological symptomsNutritional cofactors: When deficiencies perpetuate the vicious cycleVitamin DMagnesiumInositolZincOmega-3 (EPA/DHA)Why it matters for your long-term healthGlycemic riskCardiovascular riskHepatic steatosisEndometrial cancerMental healthWhat birth control can (and cannot) doIdentifying your profile: Why biomarkers change everythingWhat to rememberIn this article

PCOS: A misleading nameDiagnostic criteria: What the international guidelines say1. Hyperandrogenism2. Ovulatory dysfunction3. Polycystic ovarian morphologyDifferential diagnosis: An essential stepThe three self-reinforcing mechanismsInsulin resistance and hyperinsulinemiaChronic low-grade inflammationDysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axisThe four clinical profiles of PCOS1. Insulin resistance-dominant PCOS2. Inflammatory-dominant PCOS3. Post-contraception profile4. Adrenal-dominant PCOSThe most frequent symptomsReproductive symptomsDermatological symptoms (linked to hyperandrogenism)Metabolic symptomsPsychological symptomsNutritional cofactors: When deficiencies perpetuate the vicious cycleVitamin DMagnesiumInositolZincOmega-3 (EPA/DHA)Why it matters for your long-term healthGlycemic riskCardiovascular riskHepatic steatosisEndometrial cancerMental healthWhat birth control can (and cannot) doIdentifying your profile: Why biomarkers change everythingWhat to remember

PCOS Part 1: Understanding the condition

One of the most underdiagnosed hormonal conditionsFebruary 4, 2026Approximately 1 in 10 women is affected by polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), yet it remains one of the most under-diagnosed hormonal conditions.

Perhaps you recognize yourself: irregular or absent periods, persistent acne, creeping fatigue, stubborn weight despite all your efforts. And sometimes, a medical appointment where the term "PCOS" is mentioned without giving you a clear understanding of what it means or what it implies long-term.

Here's the central point: PCOS is not "an ovarian disease." It's an endocrine and metabolic syndrome that affects multiple systems: blood sugar and insulin, inflammation, ovulation, mood, cardiovascular health. The ovaries are often one visible manifestation, not the sole starting point.

In this edition, we provide you with a clear, structured explanation to understand what's really happening. Because understanding is the first step to taking back control.

In a second edition, we'll cover concrete solutions with a roadmap tailored to your profile.

PCOS: A misleading name

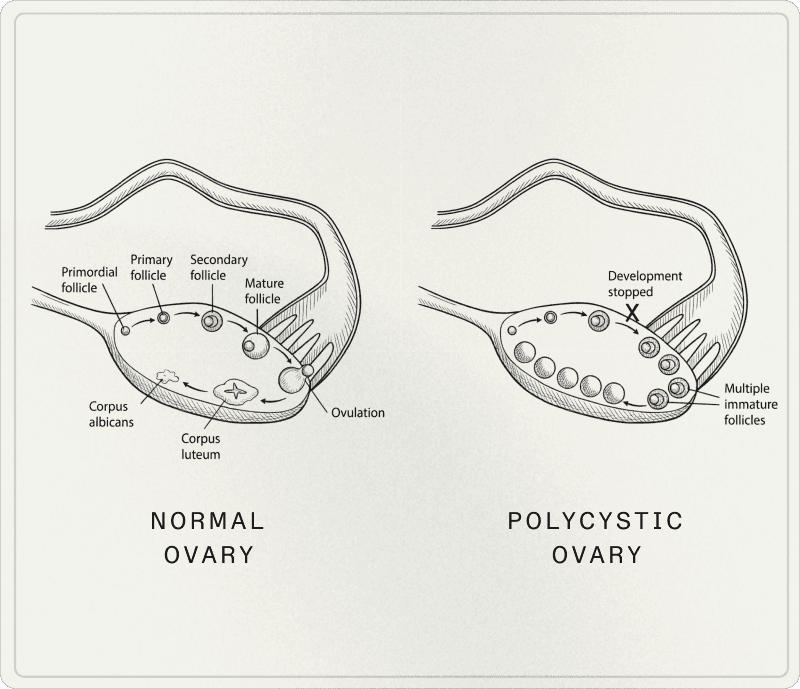

The term "polycystic ovary syndrome" is misleading. What are often called "cysts" are actually immature follicles—follicles whose growth has stopped—which have nothing to do with pathological cysts in the classical sense.

You can meet PCOS criteria without having a multifollicular appearance on ultrasound. Conversely, a so-called "polycystic" morphology can be observed in some women without being sufficient for diagnosis, especially if the overall clinical picture isn't considered.

Diagnostic criteria: What the international guidelines say

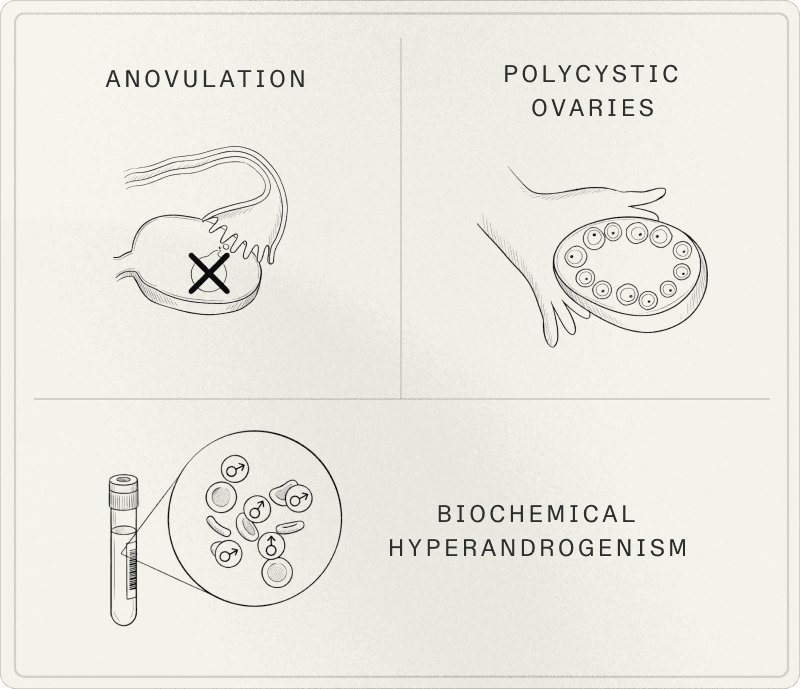

In adults, specialists rely on the Rotterdam criteria, updated and clarified in the 2023 international recommendations. The diagnosis is based on 2 out of 3 criteria, after exclusion of other causes.

1. Hyperandrogenism

Hyperandrogenism manifests either through biological signs (excess androgens in blood tests) or visible clinical signs: acne (often on the jawline, chin, back, and chest), hirsutism, androgenic alopecia, oily skin.

2. Ovulatory dysfunction

Irregular cycles (often longer than 35 days), oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, or absence of ovulation documented by basal temperature tracking, luteal phase progesterone testing, or ovulation tests.

3. Polycystic ovarian morphology

Ultrasound thresholds have evolved with imaging technology. In good-quality transvaginal ultrasound, the threshold is generally 20 or more follicles (2-9 mm) in at least one ovary, and/or an ovarian volume of 10 mL or greater.

Since 2023, AMH (anti-Müllerian hormone) can be used in adults to define polycystic morphology, but should not be used alone to diagnose PCOS.

Differential diagnosis: An essential step

Before concluding PCOS, causes that can produce similar symptoms must be excluded. PCOS is a comprehensive diagnosis, not an isolated marker.

The three self-reinforcing mechanisms

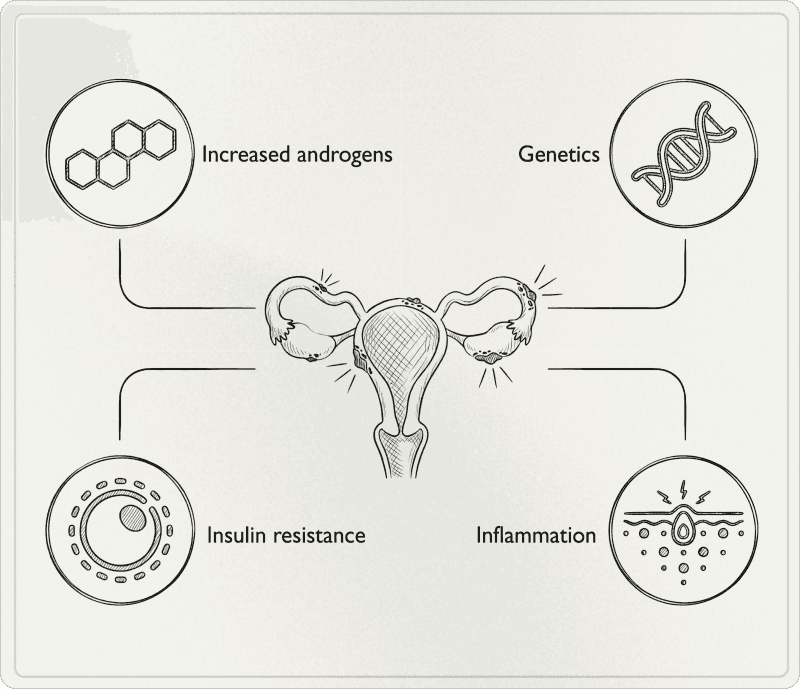

Behind the diagnostic criteria lie three interconnected axes that mutually reinforce each other: insulin, inflammation, and central and ovarian hormonal signaling.

Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia

A significant proportion of women with PCOS have insulin resistance, generally estimated between 50 and 70% depending on populations and evaluation methods. Insulin resistance means cells respond less well to insulin. To compensate, the pancreas secretes more: this is hyperinsulinemia, and it's a key point in PCOS.

Excess insulin stimulates ovarian androgen production. Simultaneously, hyperinsulinemia decreases SHBG, which increases the free (active) fraction of testosterone. Result: you can have total testosterone levels that appear normal, but elevated free testosterone that explains your symptoms.

Crucial point: insulin resistance also exists in lean women. PCOS is not a weight diagnosis, it's a diagnosis of metabolic physiology.

Chronic low-grade inflammation

Many women with PCOS have low-grade inflammation that comes from multiple sources: insulin resistance, visceral adipose tissue, sedentary lifestyle, food quality, chronic stress, sleep deprivation, digestive imbalances.

This inflammation worsens insulin resistance, amplifies certain hormonal signals, and perpetuates the "blood sugar - androgens - ovulation" cycle.

Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis

In PCOS, the hormonal "conductor" (brain + pituitary + ovaries) sends unbalanced signals. The hypothalamus sends GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) too frequently, which causes the pituitary to produce too much LH relative to FSH. This elevated LH pushes the ovary to produce more androgens and disrupts follicle maturation, making ovulation more difficult and perpetuating the hormonal vicious cycle.

We thus observe a higher LH/FSH ratio in PCOS, but it's not a diagnostic criterion per se.

Regarding prolactin: it should be measured in diagnostic workup (differential diagnosis). A slight elevation exists in about 30% of women with PCOS, but should always be interpreted with caution.

The four clinical profiles of PCOS

Research describes phenotypes according to Rotterdam criteria, but in practice we also use driver profiles that help understand what dominates the picture. These profiles are not diagnoses but help identify the main lever for targeted action.

1. Insulin resistance-dominant PCOS

This is one of the most common profiles: hyperinsulinemia, low SHBG, tendency to cravings, post-meal fatigue, abdominal fat gain. This profile also exists in lean women, confirming that PCOS is primarily a metabolic disorder, not a weight disorder.

2. Inflammatory-dominant PCOS

In this profile, low-grade inflammation is at the forefront: chronic fatigue, diffuse pain, reactive skin, frequent digestive symptoms, susceptibility to metabolic imbalances. The challenge is understanding where the inflammation comes from: blood sugar, sleep, stress, environment, digestion, or a combination of these factors.

3. Post-contraception profile

After stopping hormonal contraception, some women observe irregular cycles, acne rebound, hair loss, oily skin. Two scenarios exist: either contraception masked a pre-existing PCOS that now reappears, or the hormonal axis takes time to readjust after stopping without becoming lasting PCOS.

"Post-pill" is not a diagnosis. It's a clinical situation that requires re-establishing diagnosis with criteria, time, and appropriate biomarkers.

4. Adrenal-dominant PCOS

In this profile, excess androgens are mainly carried by the adrenal sphere (elevated DHEA-S), often in a context of chronic stress, insufficient sleep, high training load, or anxious predisposition.

Stress and PCOS don't reduce to "it's in your head." We're talking about stress biology: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis influences steroid hormone production, and therefore certain PCOS symptoms.

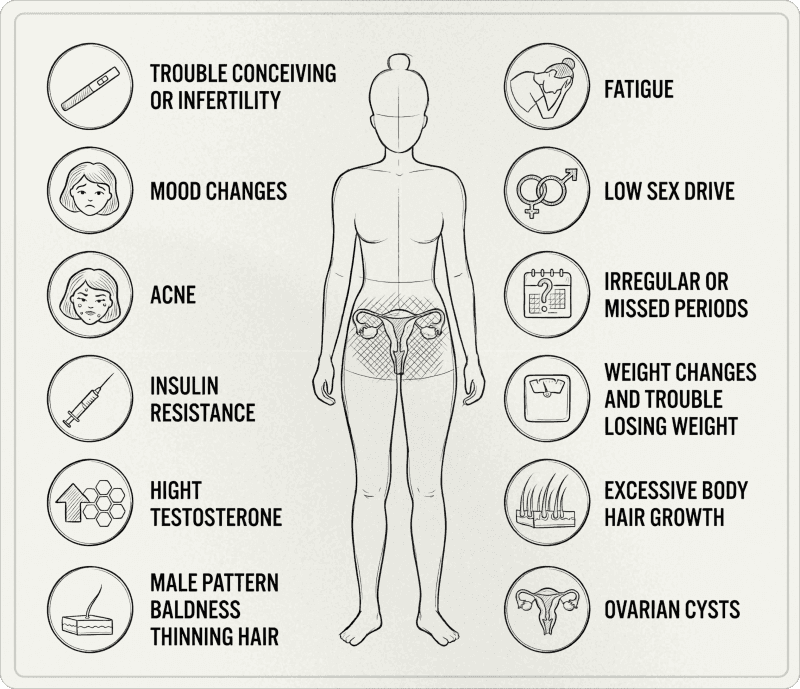

The most frequent symptoms

PCOS manifests differently from one woman to another. You don't need to have all symptoms to be affected.

Reproductive symptoms

Irregular, long cycles, or absence of periods

Anovulation confirmable by temperature tracking, luteal phase progesterone testing, or ovulation tests

Conception difficulties related to ovulatory irregularity

Pronounced premenstrual syndrome

Dermatological symptoms (linked to hyperandrogenism)

Persistent acne (often on chin, jawline, but not exclusively), oily skin

Hirsutism present in 70 to 80% of women with PCOS

Androgenic alopecia on the crown and temples

Acanthosis nigricans (areas of thickened, dark skin) in cases of marked insulin resistance

Metabolic symptoms

Possible weight gain, often abdominal, or difficulty with body recomposition

Reactive hypoglycemia and post-meal fatigue

Cravings, sugar desires

Energy "crashes"

Psychological symptoms

International guidelines emphasize: mental health is an integral part of PCOS. We observe a higher prevalence of:

Anxiety symptoms (3 to 4 times more frequent)

Depressive symptoms (3 to 4 times more frequent)

Distress related to body image

Eating disorders

This is not secondary. It's an axis to screen for and take seriously in care.

Nutritional cofactors: When deficiencies perpetuate the vicious cycle

Certain deficiencies are frequently observed in women with PCOS and amplify the syndrome's mechanisms: insulin sensitivity, inflammation, skin health, fatigue.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D deficiency is common in PCOS populations (67 to 85% according to studies). The goal is to correct documented insufficiency and achieve sufficient status. Vitamin D plays a role in insulin sensitivity, ovarian function, and inflammation regulation.

Magnesium

Magnesium is involved in glucose regulation, nervous system, and sleep. Insufficiency worsens fatigue, stress, and metabolic dysregulation. In hyperinsulinemic profiles, urinary magnesium losses are greater, creating increased need.

Inositol

Inositol (myo-inositol and D-chiro-inositol) is involved in signaling pathways related to insulin and ovulation. It can help some women with metabolic parameters and cycles, but clinical benefits vary.

Zinc

Zinc is interesting for skin, inflammation, and certain hormonal axes, especially if intakes are low or inflammatory terrain exists.

Omega-3 (EPA/DHA)

Omega-3s are relevant for inflammatory and cardio-metabolic terrain. Modern diet creates a widespread imbalance between omega-6 and omega-3, hence the interest in targeted correction.

Key message: these factors are not details. They participate in the overall biological context and must be integrated into a coherent strategy based on your profile, biomarkers, and symptoms.

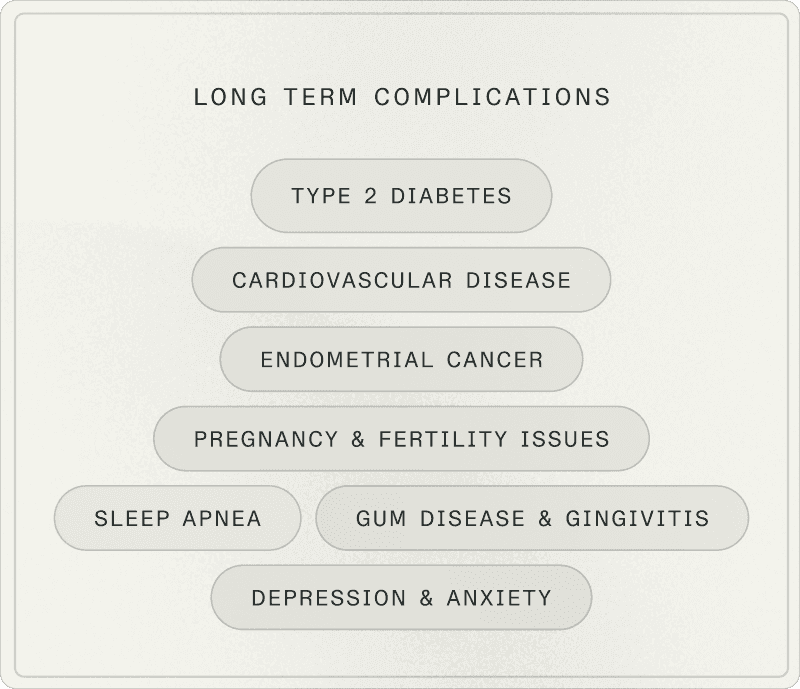

Why it matters for your long-term health

PCOS isn't just about cycles or fertility. It's a syndrome that influences your long-term metabolic health trajectory.

Glycemic risk

Women with PCOS have a 4 to 7 times higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes, often before age 40, even with normal BMI.

Cardiovascular risk

PCOS is associated with increased risk of hypertension, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and stroke, linked to insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and dyslipidemia.

Hepatic steatosis

The prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is high in women with PCOS, justifying vigilance on liver markers (ALT, AST) and metabolic profile.

Endometrial cancer

PCOS is associated with increased endometrial cancer risk, particularly with prolonged anovulation (unopposed estrogen exposure without progesterone). The 2023 recommendations specify that absolute risk remains low. Systematic screening isn't recommended: we mainly target at-risk profiles (prolonged untreated amenorrhea, overweight, diabetes, persistently thickened endometrium).

Mental health

Screening and management of psychological dimensions: anxiety, depression, quality of life, body image is paramount. The impact is major and should not be minimized.

What birth control can (and cannot) do

Hormonal contraception can improve certain visible symptoms (acne, artificially "regular" cycles) and reduce hyperandrogenism in some women. But it doesn't treat metabolic drivers: insulin, inflammation, cardio-metabolic risk.

This is why comprehensive biomarker assessment remains essential, even on contraception.

Identifying your profile: Why biomarkers change everything

To move beyond diagnostic wandering and build a personalized strategy, it's essential to objectify your profile through precise biomarkers. You can't improve what you don't measure.

Key biomarkers include:

Glucose metabolism (fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c)

Androgen hormones (total and free testosterone, DHEA-S, SHBG), ovarian hormones (LH, FSH)

Inflammation (CRP)

Liver function (ALT, AST), lipid profile (cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, LDL)

Nutritional status (vitamin D, magnesium, ferritin, B12, folate)

And thyroid (TSH, free T3, free T4)

What to remember

PCOS is an endocrine and metabolic syndrome, not "just ovaries." Diagnosis is made with precise criteria and exclusion of neighboring diagnoses. The most common drivers are insulin, inflammatory terrain, and neuro-endocrine dysregulation, with great individual variation.

Long-term risks justify a preventive, measurable, sustainable approach. Biomarkers enable moving beyond uncertainty and building a personalized strategy.

Because even though there's no definitive cure in the medical sense of PCOS, remission and symptom improvement are possible.

This is exactly what we'll see in part two: concrete action protocols and biomarkers to track.

RESSOURCES

Chen W, Pang Y. (2021). Metabolic Syndrome and PCOS: Pathogenesis and the Role of Metabolites. Metabolites, 11(12), 869.

Cooney LG, Dokras A. (2017). Psychological aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 35(3), 238–248.

Dokras A, et al. (2011). Depression, anxiety and quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecological Endocrinology, 27(10), 787–793.

Dunaif A. (1997). Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. Endocrine Reviews, 18(6), 774–800.

Escobar-Morreale HF, et al. (2005). The polycystic ovary syndrome associated with morbid obesity may resolve after weight loss induced by bariatric surgery. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(12), 6364–6369.

Greenwood EA, et al. (2018). Association of depression with the polycystic ovary syndrome symptom experience, quality of life, and body mass index. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 219(4), 1–7.

Harrison CL, et al. (2011). Exercise therapy in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 17(2), 171–183.

International PCOS Network. (2023). International evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome 2023. Monash University (MCHRI).

Joham AE, et al. (2022). Polycystic ovary syndrome. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10(9), 668–680.

Legro RS, et al. (2013). Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(12), 4565–4592.

March WA, et al. (2010). The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(5), 2038–2049.

Moran LJ, et al. (2010). Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 16(4), 347–363.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. (2004). Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility, 81(1), 19–25.

Soffer D, et al. (2024). Role of apoB in clinical management of cardiovascular risk in adults: an expert clinical consensus from the National Lipid Association. Journal of Clinical Lipidology.