In this article

2. Physical activity: Move intelligentlyFocus on:3. Stress and sleep management: Hormonal regulatorsManaging chronic stressOptimize sleepPCOS and severe premenstrual disordersBeware of sleep apnea4. Biomarkers to track: Measure to progressGlucose metabolism and insulin resistanceAndrogens and transportOvarian hormonesInflammationLiver functionLipid profileNutritional statusThyroidHow often?5. Supplementation: Targeted correctionThe essentialsWhat to remember about supplementationConclusion: Your roadmapIn this article

2. Physical activity: Move intelligentlyFocus on:3. Stress and sleep management: Hormonal regulatorsManaging chronic stressOptimize sleepPCOS and severe premenstrual disordersBeware of sleep apnea4. Biomarkers to track: Measure to progressGlucose metabolism and insulin resistanceAndrogens and transportOvarian hormonesInflammationLiver functionLipid profileNutritional statusThyroidHow often?5. Supplementation: Targeted correctionThe essentialsWhat to remember about supplementationConclusion: Your roadmap

PCOS Part 2: Concrete Solutions

Nutrition, activity, and sleep to better manage PCOS February 4, 2026In part one, we decoded PCOS mechanisms and why each woman has a unique profile. You now know that PCOS is a metabolic and hormonal syndrome that can be addressed by tackling underlying mechanisms.

Now, let's take action.

This second part presents concrete interventions to act on PCOS's main levers: insulin sensitivity, chronic inflammation, and hormonal balance.

Important: these recommendations don't replace medical follow-up. They constitute preventive and educational support to help you regain control of your metabolic and hormonal health.

Nutrition: The first lever (and the most powerful)

Diet directly affects insulin, inflammation, and androgen production. It's not about restriction, but construction: each meal is an opportunity to stabilize your metabolism.

1- Stabilize blood sugar

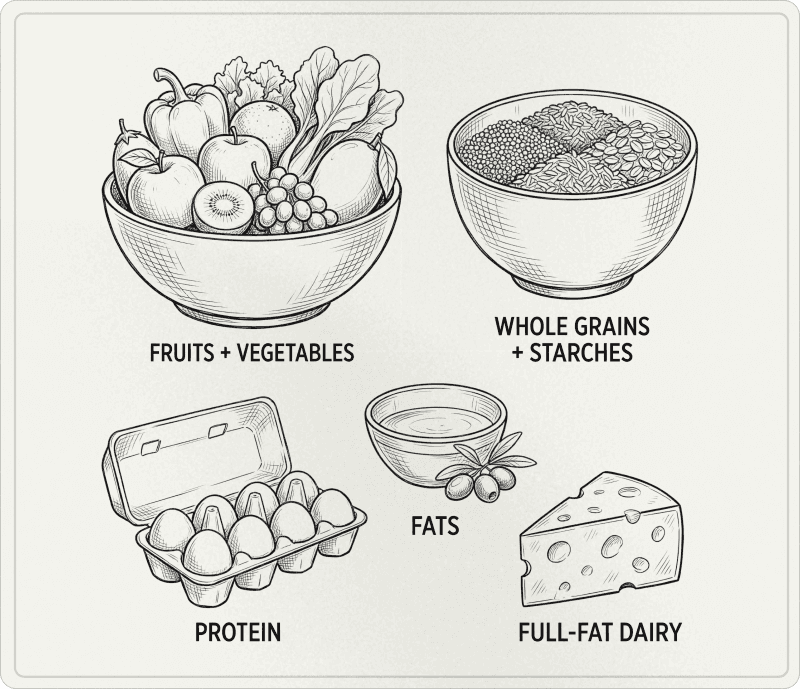

The goal is to reduce insulin spikes, even when blood sugar seems normal. At each meal, build your plate around four pillars:

Protein ~25-35g per meal: eggs, fish, poultry, tofu, tempeh, Greek yogurt or skyr if tolerated, legumes

Fiber: vegetables, whole fruits, legumes, seeds

Quality fats: olive oil, avocado, nuts, fatty fish

This combination slows carbohydrate absorption, stabilizes blood sugar, improves satiety, and reduces cravings.

Whole carbohydrates with low to moderate glycemic index: legumes, quinoa, buckwheat, sweet potato, basmati or brown rice if tolerated, whole fruits (particularly berries, kiwi, citrus).

2- Reduce inflammation through food

Increase whole foods

Favor gentle cooking methods

Integrate dietary omega-3s (sardines, mackerel, salmon)

Use anti-inflammatory spices (turmeric, ginger)

Consume polyphenols (berries, green tea)

Reduce alcohol consumption, added sugars, and processed foods

The real anti-inflammatory isn't an isolated superfood, it's daily repetition of coherent choices.

2. Physical activity: Move intelligently

Exercise improves insulin sensitivity and supports hormonal balance, independent of weight loss.

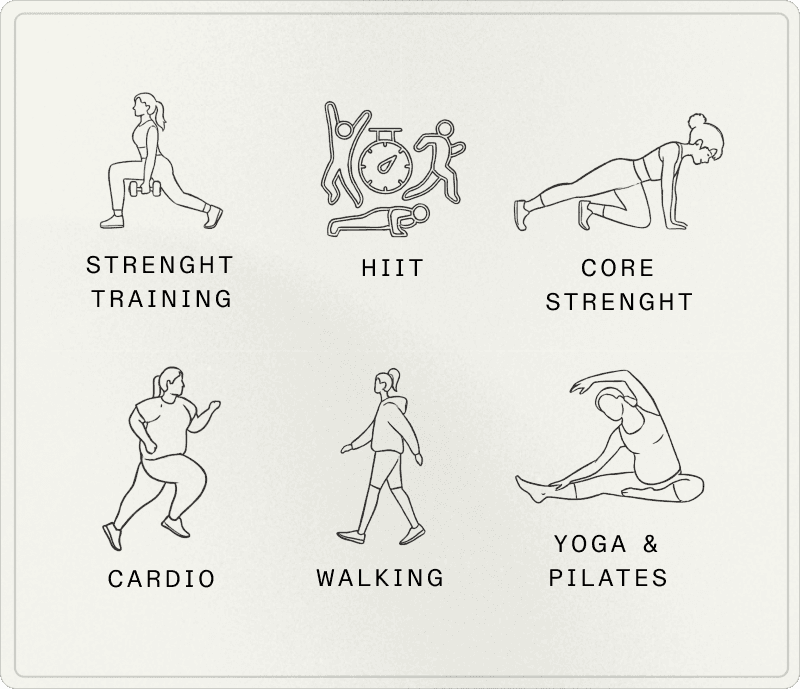

Focus on:

Strength training: 3-4 times per week

Strength training increases muscle mass, which directly improves glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity. Muscles are the main glucose reservoirs in the body.

Free weights, machines, bodyweight exercises (squats, lunges, push-ups, pull-ups). Aim for 30-45 minute sessions, with regular progression.

Daily walking: The underestimated weapon

Walking after meals (ideally 10-15 minutes) is simple, accessible, and very effective for regulating post-meal blood sugar without stressing the body. It's one of the most powerful and underused tools.

Some HIIT: Short and spaced

Sessions of 15-20 minutes maximum, 1-2 times per week. Short, intense intervals (20-30 seconds of intense effort, followed by 60-90 seconds of recovery) effectively improve insulin sensitivity without generating excessive stress.

If you have an adrenal profile or chronic stress, prioritize strength training and walking before adding HIIT.

What to avoid

Too many prolonged moderate-intensity cardio sessions that can worsen adrenal stress, particularly if you're already in a chronic stress situation. It seems counterintuitive, but more cardio of this type won't necessarily mean better results.

Overtraining. If your cycles lengthen, your sleep deteriorates, hunger explodes, and recovery is poor, it's not lack of willpower. It's often poorly calibrated training load. Balance is key: enough to stimulate, not too much to exhaust.

💡 Tracking tool: Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

HRV measures the interval between your heartbeats and reflects the state of your nervous system. It's an excellent indicator of recovery and stress tolerance:

High HRV = good recovery state, balanced nervous system, preserved stress tolerance

Low or declining HRV = signal of fatigue, chronic stress, insufficient recovery, potential overtraining

You can track your HRV with a watch or trackers like Whoop, Oura, connected devices. A progressive decline in your HRV over several days is a clear signal that you need to reduce training intensity or volume, prioritize rest, or improve your stress and sleep management.

3. Stress and sleep management: Hormonal regulators

Chronic stress and sleep deprivation directly disrupt your hormones, particularly cortisol, which worsens insulin resistance and stimulates DHEA-S production by the adrenals.

Managing chronic stress

International guidelines integrate mental health (anxiety, depression, body image, quality of life) as an evaluation and care axis for PCOS. It's not "in your head," it's biological reality.

Validated techniques:

Heart rate coherence: 5 minutes, 3 times daily (breathing: 5 seconds in, 5 seconds out). Reduces cortisol, improves heart rate variability.

Mindfulness meditation: 10-20 minutes daily. Reduces anxiety, improves emotional regulation, reduces inflammation.

Gentle or restorative yoga: activates parasympathetic nervous system (rest and repair), reduces cortisol.

Nature walks: 20-30 minutes daily. Reduces cortisol, improves mood.

Identify and reduce chronic stress sources

These techniques are important, but sometimes you need to identify and change the source: toxic relationship, work overload, perfectionism, social isolation. Identifying these factors is as important as any other nutritional or physical intervention.

Optimize sleep

Sleep deprivation (less than 7 hours per night) worsens insulin resistance, increases ghrelin (hunger hormone), reduces leptin (satiety), and disrupts hormonal production.

Sleep hygiene:

Regular schedule: go to bed and wake up at the same time, even on weekends

Reduce blue light: avoid screens 1-2h before bed, or use blue light blocking glasses

Cool temperature: 18-19°C in bedroom promotes sleep onset

Magnesium before bed: promotes relaxation and improves sleep quality

Calming routine: reading, herbal tea, gentle stretching, warm bath

PCOS and severe premenstrual disorders

Recent data suggest an association between PCOS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). If your premenstrual symptoms are very disabling, this deserves to be named, evaluated, and managed, not dismissed.

Beware of sleep apnea

The risk of obstructive sleep apnea is higher in women with PCOS. If you have snoring, daytime sleepiness, or restless sleep, talk to your doctor.

4. Biomarkers to track: Measure to progress

You can't improve what you don't measure. Identifying your hormonal and metabolic profile through precise biomarkers allows you to adjust interventions and track progress.

Glucose metabolism and insulin resistance

Fasting glucose, fasting insulin

HOMA-IR: calculated from fasting glucose and insulin

HbA1c: reflection of 3-month blood sugar

Androgens and transport

Total testosterone

Free testosterone

DHEA-S (adrenal origin)

SHBG

Ovarian hormones

LH and FSH: measured in early follicular phase (cycle day 2-5)

LH/FSH ratio: ratio >2 or 3 suggests PCOS, but not diagnostic alone

Inflammation

CRP (C-reactive protein): systemic inflammation marker

Liver function

ALT and AST

Lipid profile

Total cholesterol

LDL-C, HDL-C

Triglycerides

Nutritional status

Vitamin D (25-OH-vitamin D)

Magnesium

Ferritin

B12

Folate

Thyroid

TSH

Free T3

Free T4

PCOS often coexists with thyroid disorders (particularly Hashimoto's).

How often?

5. Supplementation: Targeted correction

Supplementation never replaces quality nutrition, but it can correct specific deficiencies and accelerate remission.

The essentials

Inositol (myo-inositol + D-chiro-inositol)

Myo-inositol ideally combined with D-chiro-inositol in a 40:1 ratio. Improves insulin sensitivity, reduces androgens, improves egg quality. Studies show benefits in some women, particularly on metabolic parameters and cycles.

Vitamin D3 (if deficient)

Deficiency is very common in women with PCOS (67-85%). The goal is to correct documented insufficiency. Improves insulin sensitivity, reduces inflammation, supports ovarian function.

Magnesium

Bioavailable forms: glycinate, bisglycinate, malate. Improves insulin sensitivity, reduces anxiety, improves sleep. In hyperinsulinemic profiles, urinary magnesium losses are greater.

Omega-3 (EPA + DHA)

Reduces inflammation, improves insulin sensitivity, improves lipid profile. Particularly relevant if triglycerides are elevated or fatty fish consumption is low.

What to remember about supplementation

Always test your biomarkers before and after to adjust

Favor quality: bioavailable forms, third-party tested brands

Don't take everything at once: start gradually and observe effects

Supplementation alone isn't enough, it accompanies adapted diet and lifestyle

Conclusion: Your roadmap

PCOS is a signal your body sends you, and you now have some keys to better understand it.

Your journey, step by step:

1. Consult a healthcare professional PCOS diagnosis and surveillance require medical support. Your doctor, gynecologist, endocrinologist, or midwife can:

Make the diagnosis

Exclude other causes (thyroid, hyperprolactinemia, etc.)

Prescribe appropriate biological tests

Ensure medical follow-up adapted to your situation

2. Get a complete panel of your biomarkers To identify your specific profile (glucose metabolism, androgen hormones, inflammation, liver, lipids, nutritional status, thyroid).

3. Implement preventive pillars

Nutrition: blood sugar stabilization and inflammation reduction

Physical activity: strength training + daily walking + activity adapted to your stress level

Sleep and stress: as important as nutrition

Targeted supplementation: based on your documented deficiencies and unique profile

4. Track your progress Reassess your biomarkers at 6 months to adjust your strategy.

PCOS symptom improvement is possible. It requires time, consistency, a comprehensive approach, and adapted medical support. But each adjustment you make is a step toward hormonal and metabolic balance.

You're taking back control.

This content is preventive and educational support that complements, and does not replace, medical follow-up.

Sources and Scientific References

Chen W, Pang Y. (2021). Metabolic Syndrome and PCOS: Pathogenesis and the Role of Metabolites. Metabolites, 11(12), 869.

Cooney LG, Dokras A. (2017). Psychological aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 35(3), 238–248.

Dokras A, et al. (2011). Depression, anxiety and quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecological Endocrinology, 27(10), 787–793.

Dunaif A. (1997). Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. Endocrine Reviews, 18(6), 774–800.

Escobar-Morreale HF, et al. (2005). The polycystic ovary syndrome associated with morbid obesity may resolve after weight loss induced by bariatric surgery. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(12), 6364–6369.

Greenwood EA, et al. (2018). Association of depression with the polycystic ovary syndrome symptom experience, quality of life, and body mass index. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 219(4), 1–7.

Harrison CL, et al. (2011). Exercise therapy in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 17(2), 171–183.

International PCOS Network. (2023). International evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome 2023. Monash University (MCHRI).

Joham AE, et al. (2022). Polycystic ovary syndrome. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10(9), 668–680.

Legro RS, et al. (2013). Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(12), 4565–4592.

March WA, et al. (2010). The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(5), 2038–2049.

Moran LJ, et al. (2010). Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 16(4), 347–363.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. (2004). Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility, 81(1), 19–25.

Soffer D, et al. (2024). Role of apoB in clinical management of cardiovascular risk in adults: an expert clinical consensus from the National Lipid Association. Journal of Clinical Lipidology.