In this article

What really happens when you drinkThe metabolic chain (and why it matters)Why it disrupts multiple systems simultaneouslyThe 4 systems impacted by alcohol1. Brain: the neurochemical debt2. Sleep: when sedation doesn't mean recovery3. Gut: the barrier → immunity → brain cascade4. Hormones: the silent disruptionThe vicious circleDry January: what can objectively change in 30 daysHow to succeed: concrete strategiesThe essential takeaway🧪 Measure the real impact with Lucis🎙️ To go further: a special alcohol episode with Dr. Pauline JumeauSCIENTIFIC REFERENCESIn this article

What really happens when you drinkThe metabolic chain (and why it matters)Why it disrupts multiple systems simultaneouslyThe 4 systems impacted by alcohol1. Brain: the neurochemical debt2. Sleep: when sedation doesn't mean recovery3. Gut: the barrier → immunity → brain cascade4. Hormones: the silent disruptionThe vicious circleDry January: what can objectively change in 30 daysHow to succeed: concrete strategiesThe essential takeaway🧪 Measure the real impact with Lucis🎙️ To go further: a special alcohol episode with Dr. Pauline JumeauSCIENTIFIC REFERENCES

Dry January: What Alcohol Really Does to Your Body (From the First Drink)

We are often told to practice ‘moderate consumption.’February 3, 2026The holidays are ending, January is here, and with it comes the famous Dry January. You may have drunk a bit more than usual these past few weeks, and now you're wondering if it's time to "take a break" and whether it would really make a difference.

The problem with alcohol is that the messaging is contradictory. We've long been told that a glass of red wine a day is good for the heart. We're told about "moderate consumption" without really defining what that means. We're reassured that "it's all about the dose."

But what's rarely explained are the precise biological mechanisms that kick in from the very first drink, and why even moderate consumption has measurable effects on your brain, sleep, gut, and hormones.

What really happens when you drink

One standard drink = 10g of pure alcohol (25cl beer, 10cl wine, 3cl spirits).

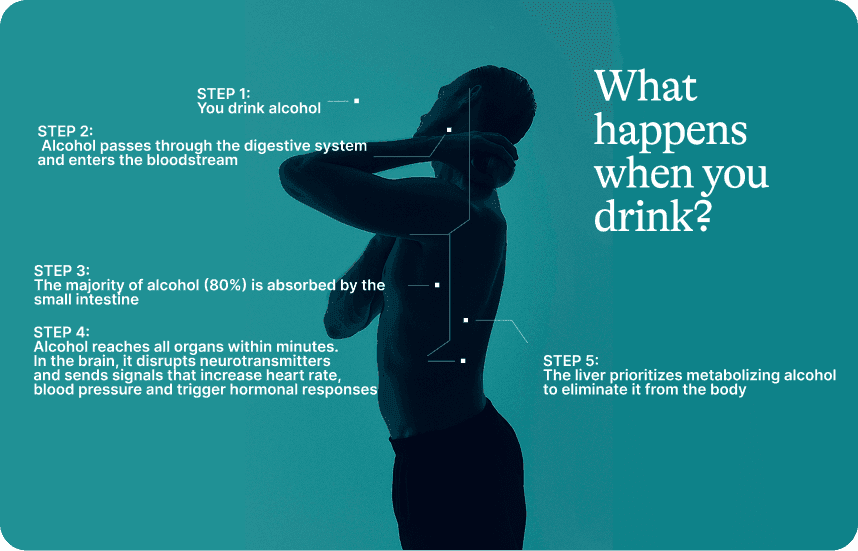

When you consume alcohol, you're ingesting ethanol. Your body can neither store it nor use it as is. It must eliminate it immediately. Alcohol metabolism becomes priority over everything else: digestion, tissue repair, hormonal regulation all take a back seat.

The metabolic chain (and why it matters)

Ethanol → Acetaldehyde → Acetate

Two enzymes orchestrate this transformation:

ADH (alcohol dehydrogenase): converts ethanol to acetaldehyde

ALDH (aldehyde dehydrogenase): converts acetaldehyde to acetate

The key point: It's not the ethanol that causes most of the damage. It's acetaldehyde, the intermediate metabolite. It's a highly reactive compound, classified as carcinogenic, that creates genetic mutations, generates oxidative stress, and causes inflammation and cellular destruction.

Significant genetic variability: Some people (particularly of East Asian descent) have ALDH2 variants that slow conversion. Result: acetaldehyde accumulation, facial flushing, palpitations. It is a biological signal of toxic accumulation.

Why it disrupts multiple systems simultaneously

1. Alcohol penetrates everywhere

Alcohol is both water-soluble and fat-soluble. This dual property allows it to cross all cell membranes effortlessly and penetrate directly into your cells: brain, gut, liver, muscles, hormonal tissues.

Unlike other substances that remain confined to certain organs, alcohol diffuses throughout your entire body within minutes.

2. It disrupts metabolism

Every time a cell metabolizes alcohol, it consumes NAD⁺ (an essential cofactor for your cellular reactions) and produces NADH.

Ethanol (+ NAD⁺) → Acetaldehyde (+ NADH) Acetaldehyde (+ NAD⁺) → Acetate (+ NADH)

Result: the NAD⁺/NADH ratio collapses. Cells lack NAD⁺ to run their normal metabolic functions.

Immediate consequences:

Glucose production slowed: The liver needs NAD⁺ to produce glucose → possible hypoglycemia (nighttime awakenings, cravings)

Fat burning blocked: Mitochondria need NAD⁺ to burn fatty acids → accumulation in the liver

Fat synthesis increased: Excess acetyl-CoA is redirected toward producing new fatty acids

Simple translation: Alcohol reaches all your organs + it disrupts their energy metabolism = simultaneous disruption of brain, liver, gut, hormones. Your body puts its normal functions on pause to deal with this toxic molecule urgently.

The 4 systems impacted by alcohol

Even at low doses, alcohol simultaneously affects several interconnected systems.

1. Brain: the neurochemical debt

When you drink, your brain releases a rapid spike of dopamine and serotonin. This creates the pleasant, relaxed, sociable sensation.

The problem: this spike is followed by a prolonged drop. In the hours and days that follow, your levels remain below your baseline. This isn't psychological: it's an automatic neurochemical compensation.

What this explains:

Next-day anxiety ("hangxiety")

Irritability, brain fog

Reduced motivation

Alcohol also temporarily deactivates the prefrontal cortex (decision-making, impulse control). This is why your judgment becomes impaired.

What the data shows:

A study of 36,678 adults (UK Biobank) shows a dose-response association between alcohol consumption and reduced brain volume, even at "moderate" levels (7-14 drinks/week). Most affected regions: hippocampus (memory) and prefrontal cortex.

→ What really matters: speed

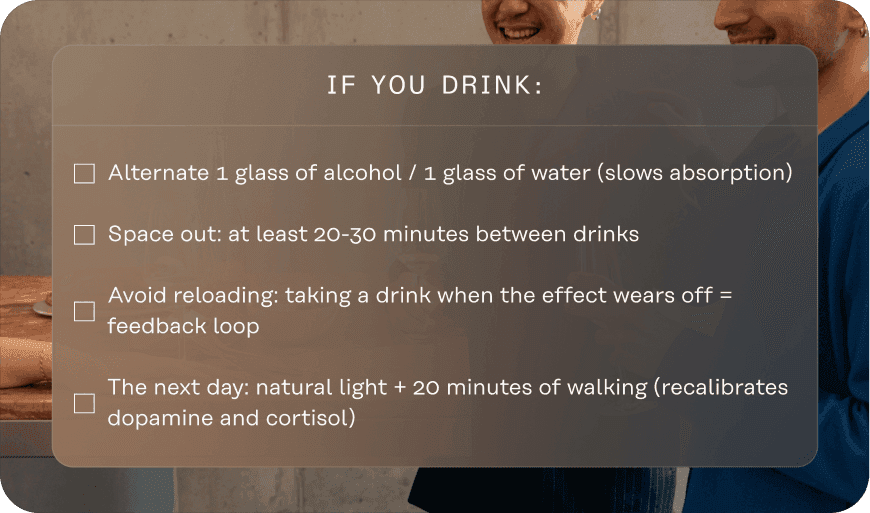

Two drinks in 30 minutes don't have the same impact as two drinks over 2 hours. Speed determines the peak blood concentration and the intensity of the neurochemical rebound.

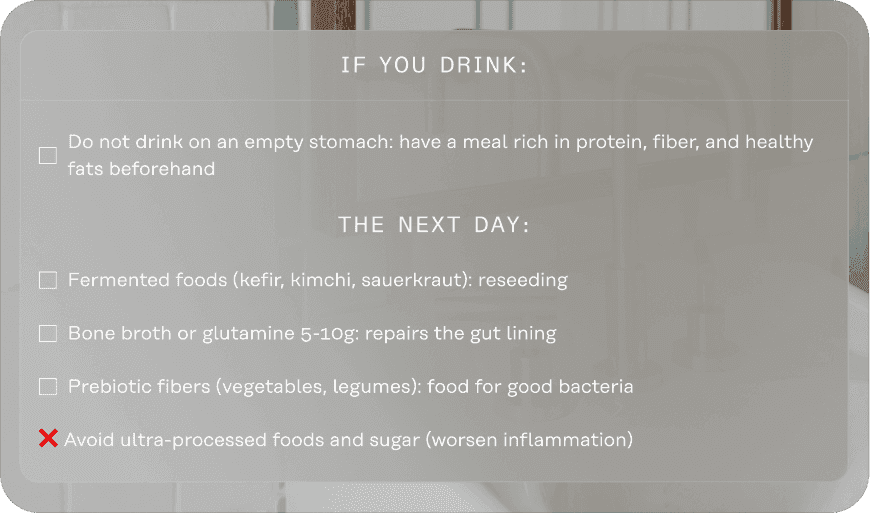

If you drink:

2. Sleep: when sedation doesn't mean recovery

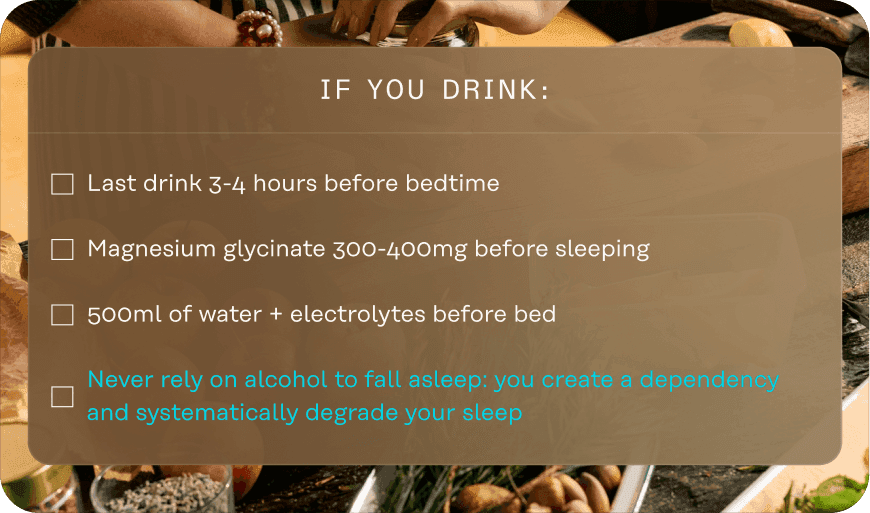

Alcohol helps you fall asleep faster. That's true. But pharmacological sedation ≠ restorative sleep.

What happens during the night:

First half: "heavier" sleep (sedation), but not necessarily deep Second half: massive fragmentation, frequent micro-awakenings, quality collapses

Alcohol:

Blocks access to deep sleep (physical repair, brain toxin clearance)

Reduces REM sleep (emotional processing)

Causes micro-awakenings that prevent you from diving into restorative phases

Result: you sleep 8 hours, but wake up tired. Biologically, nothing recharged.

Why these nighttime awakenings?

Neurochemical rebound effect: When alcohol is metabolized, glutamate (excitatory) surges back. Your brain "wakes up" chemically.

Glycemic dysregulation: The liver, busy metabolizing alcohol, regulates nighttime blood sugar less effectively. If it drops, the body releases cortisol and adrenaline → awakening between 2-4am.

Alcohol also worsens snoring and apnea (muscle relaxation), further fragmenting sleep.

→ Timing is more critical than quantity

A drink at 7pm doesn't have the same impact as a drink at 10pm. Alcohol has a half-life of 4-5 hours. The later you drink, the more active it is during your night.

If you drink:

3. Gut: the barrier → immunity → brain cascade

Alcohol profoundly disrupts the intestinal ecosystem through several mechanisms:

What happens in cascade:

Alcohol alters microbial composition (reduction of protective strains)

It damages tight junctions between intestinal cells

The barrier becomes more permeable

Bacterial fragments pass into the bloodstream

The immune system activates an inflammatory response

Hepatic alcohol metabolism simultaneously triggers production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Inflammation becomes systemic.

What this concretely explains:

Brain fog and "unexplained" fatigue the next day

More labile mood (90% of serotonin is produced in the gut)

Sensitive digestion, bloating

Dull skin, redness

The most inflammatory combo: Alcohol + sugar + sleep deprivation.

→ Actively care for the intestinal barrier

If you drink:

4. Hormones: the silent disruption

Alcohol disrupts two major hormonal axes.

The stress axis (HPA):

Even moderate consumption increases your baseline cortisol. Not just the evening you drink, but chronically if you drink regularly.

Mechanism: Alcohol → fragmented sleep → elevated cortisol upon waking → stress hypersensitivity → urge to "decompress" → alcohol. The vicious circle.

Result: increased stress sensitivity, irritability, reduced recovery.

The testosterone-estrogen balance:

Alcohol increases the activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone to estrogen.

In men: reduced libido, abdominal fat storage In women: hormonal imbalance, worsened PMS

The cancer link:

Alcohol is causally linked to at least 7 types of cancer, including breast cancer (risk +4-13% per drink/day).

Mechanisms: acetaldehyde toxicity (genetic mutations), oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, hormonal disruptions.

Crucial point: Health authorities (WHO, HHS) converge: no demonstrated "risk-free" threshold.

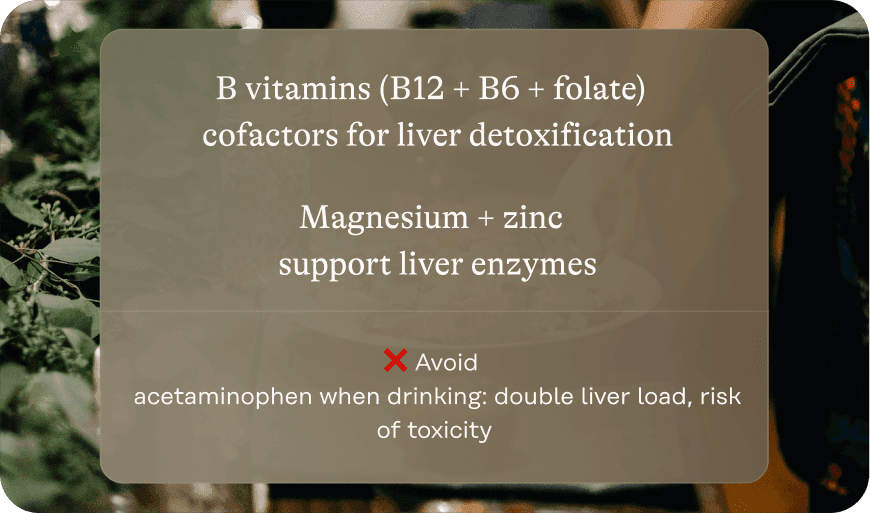

→ Support hepatic detoxification

The vicious circle

These four systems feed each other:

Alcohol → fragmented sleep → elevated cortisol → unstable blood sugar → cravings → unbalanced microbiome → inflammation → anxiety, brain fog → urge to decompress → alcohol.

Even at "moderate" doses (7-14 drinks/week), multiple systems are under chronic pressure. You may feel "fine" but notice that your energy, mental clarity, and resilience aren't what they used to be.

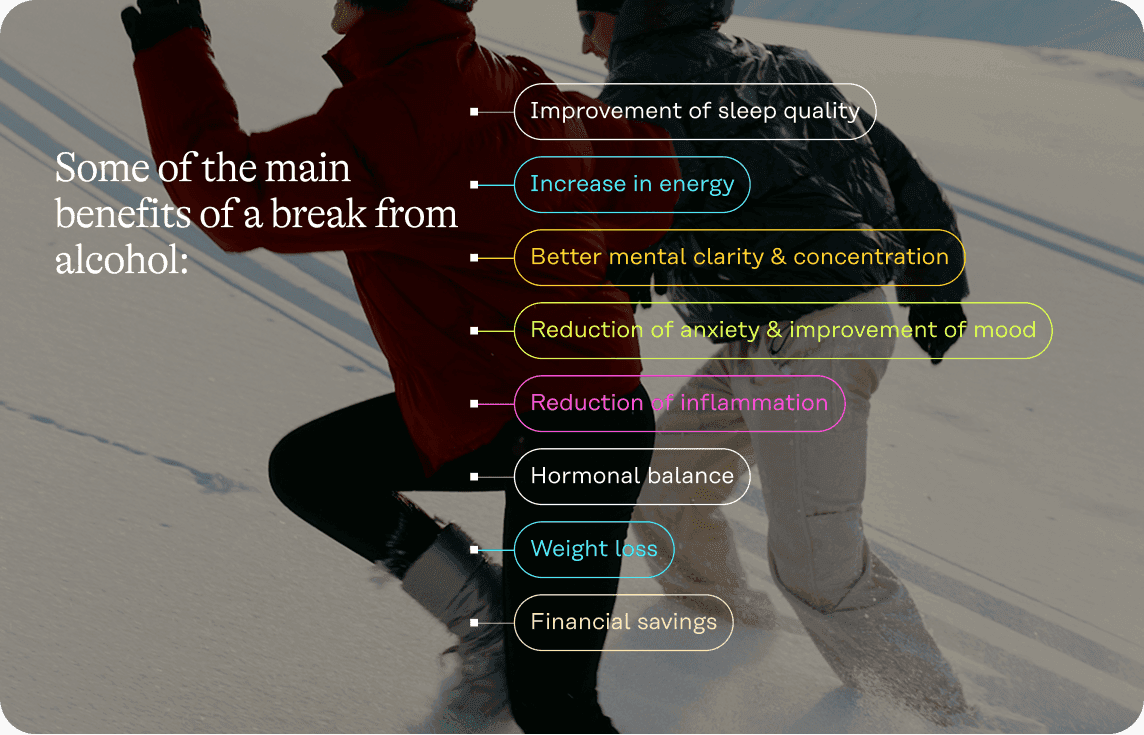

Dry January: what can objectively change in 30 days

Stopping alcohol for a month allows several systems to begin recovering. Speed varies depending on your initial consumption, genetics (ALDH2 variants), and overall health status.

What studies document:

After 4-6 weeks of abstinence:

Improvement in liver biomarkers (GGT, transaminases)

Reduction in systemic inflammation (hsCRP)

Improved insulin sensitivity

Partial microbiome regeneration

What you may observe:

More continuous and deep sleep (after 1-2 weeks)

More stable energy throughout the day

Less floating anxiety

Improved mental clarity

Clearer skin

Weight loss (if regular consumption)

How to succeed: concrete strategies

Identify your automatisms: Alcohol invites itself into routines (Friday aperitif, dinner wine, decompression after a hard day). Name the context, emotion, function. Anticipate the moments.

Replace the ritual: Your brain seeks dopamine and sensory richness. Give it that differently: elaborate mocktails, artisanal kombucha, premium tea in a beautiful cup, sparkling water with lemon and fresh mint. The ritual matters as much as the content.

Adjust your environment: Stock accessible alternatives. Socially: arrive with your drink, order first to avoid pressure, be direct ("I'm taking a break this month, testing the impact on my energy").

Find your why: "I want to wake up with energy," "I want to see if my anxiety decreases," "I want to prove I can." Write it down. Reread it. Why always precedes how.

Track your progress: Consecutive days, money saved, sleep quality (1-10 scale), 3pm energy, mental clarity. What's measured improves. Documentation creates motivation.

Find allies: Do it with a friend, join a sober-curious group, share your progress. Social support transforms individual effort into shared experience and strengthens commitment.

The essential takeaway

There is no scientifically proven "risk-free" dose of alcohol. Even moderate consumption has measurable effects on the brain, sleep, gut, and hormones.

If you choose to drink, mitigation strategies attenuate some effects. They don't eliminate them.

Dry January can be a moment to question our relationship with alcohol and experiment without it!

The goal isn't to become abstinent for life (unless that's your choice). The goal is to understand. Then you decide with full knowledge.

🧪 Measure the real impact with Lucis

To objectify changes beyond subjective feeling, test your biomarkers before and after Dry January.

A Lucis panel measures:

Liver: GGT, ALT, AST (hepatic load)

Inflammation: hsCRP (systemic inflammation)

Metabolism: glucose, insulin, HbA1c, HOMA-IR (insulin sensitivity)

Lipids: triglycerides, HDL, ApoB

Cortisol: stress profile

Hormones: testosterone, estrogen.

You'll know exactly where your body is recovering and what needs support.

🎙️ To go further: a special alcohol episode with Dr. Pauline Jumeau

With Dr. Pauline Jumeau, PharmD specialized in biohacking & functional health, we dissect metabolic mechanisms and science-based mitigation strategies.

SCIENTIFIC REFERENCES

Zakhari, S. (2006). Overview: How is alcohol metabolized by the body? Alcohol Research & Health, 29(4), 245-254.

Topiwala, A., et al. (2022). Associations between moderate alcohol consumption, brain iron, and cognition. Nature Communications, 13, 1175.

Ebrahim, I.O., et al. (2013). Alcohol and sleep I: Effects on normal sleep. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(4), 539-549.

Engen, P.A., et al. (2015). The gastrointestinal microbiome: Alcohol effects. Alcohol Research, 37(2), 223-236.

Scoccianti, C., et al. (2016). Female breast cancer and alcohol consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(3), 398-407.

Brooks, P.J., et al. (2009). The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer. PLoS Medicine, 6(3), e1000050.

Mehta, A.J., et al. (2018). Short-term abstinence from alcohol and changes in cardiovascular risk factors. BMJ Open, 8(5), e020673.