In this article

What’s really behind your fatigue1. Chronic stress: allostatic load (when the system wears out)When the bill piles up: allostatic loadWhat’s happening in the body, concretely2. Blood sugar rollercoaster: when energy crashesA word on carbs (and why they’re not all the same)The explosive duo: cortisol + glucoseReactive hypoglycaemia: the crash after the spike3 habits to reduce allostatic load now1. Protect a few real nights of repair2. Structure meals to reduce the rollercoaster3. Bring stress down every day (5–10 minutes is enough)4. Making your allostatic load visibleIn this article

What’s really behind your fatigue1. Chronic stress: allostatic load (when the system wears out)When the bill piles up: allostatic loadWhat’s happening in the body, concretely2. Blood sugar rollercoaster: when energy crashesA word on carbs (and why they’re not all the same)The explosive duo: cortisol + glucoseReactive hypoglycaemia: the crash after the spike3 habits to reduce allostatic load now1. Protect a few real nights of repair2. Structure meals to reduce the rollercoaster3. Bring stress down every day (5–10 minutes is enough)4. Making your allostatic load visible

Why You Feel Exhausted at the End of the Year

…and 3 habits to recharge before the holiday marathonFebruary 4, 2026You’re about to chain together: final projects, team dinners, Christmas planning, travel, gifts, family meals.

And you can feel it: you’ve got no margin left.

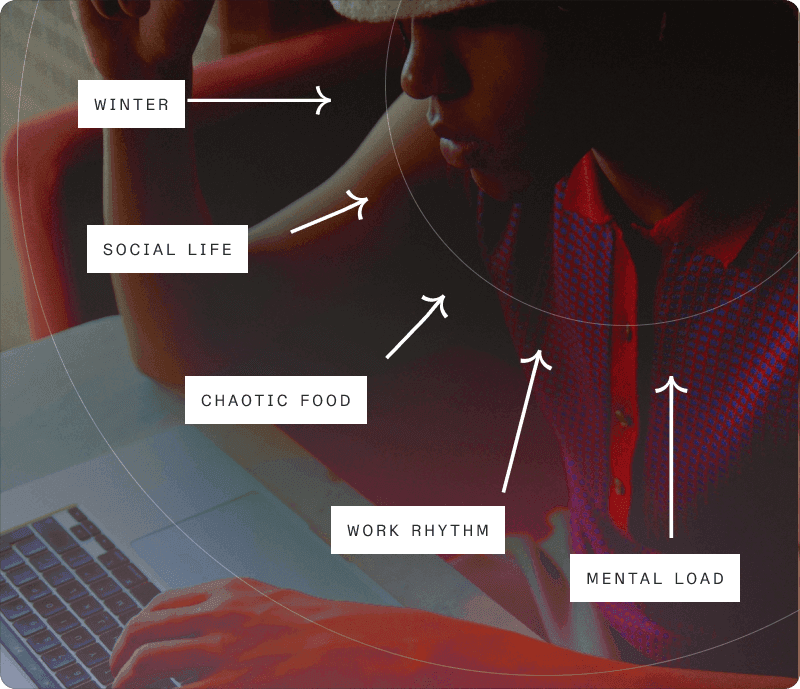

December concentrates a lot of factors that put your nervous system, hormones and metabolism under pressure all at once.

Today, we’re going to talk about a key concept: allostatic load – the biological “bill” your body pays when it has to adapt constantly – and what you can put in place before 2026.

What’s really behind your fatigue

A simple “I’m wiped” can hide several mechanisms.

The more you understand the why, the more precisely you can act.

1. Chronic stress: allostatic load (when the system wears out)

In physiology, we distinguish two notions:

Homeostasis: the body’s ability to keep things stable

(e.g. temperature at 37°C / 98.6°F).

Allostasis: the body’s ability to change to meet a demand

(e.g. producing cortisol and adrenaline when facing a threat or a deadline).

When you face a stressor, your body:

releases cortisol + adrenaline into the blood,

mobilises sugar, increases alertness, accelerates heart rate,

then, once the threat is gone, everything comes down → back to baseline.

That’s normal… as long as it’s occasional.

When the bill piles up: allostatic load

Allostatic load is what happens when:

the alarm system is activated too often,

or when it never really switches off.

Each activation has an energy cost.

Your body has a limited energy budget. When it constantly has to pay to:

get you through the day,

handle urgencies,

compensate for lack of sleep,

it cuts the budget for “long-term projects”:

repairing tissues,

building muscle,

digesting and absorbing properly,

defending the body against infections,

making hormones like DHEA, testosterone, oestrogens.

If the load is too high for too long → deep fatigue, pain, recurrent infections, feeling like you’re ageing faster.

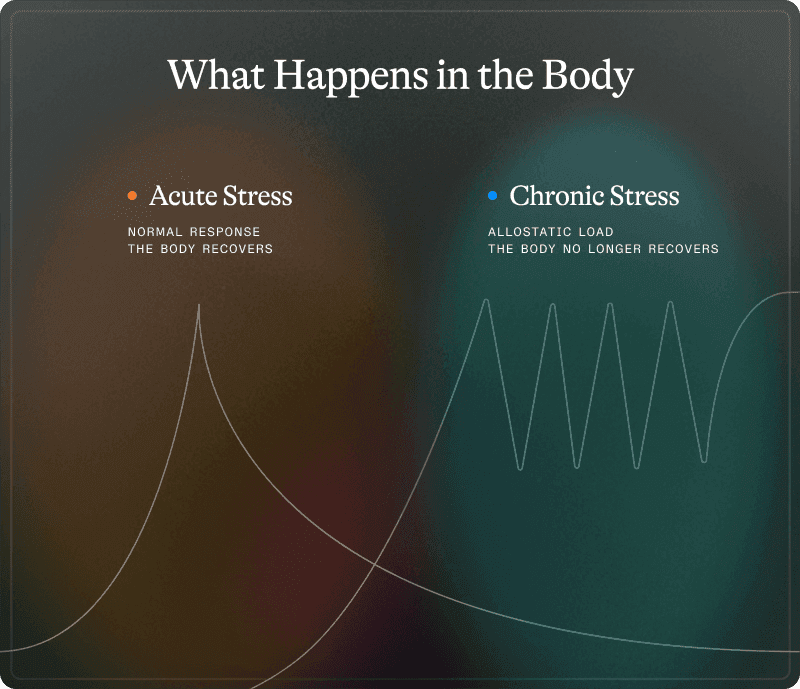

What’s happening in the body, concretely

In a normal situation:

stress → cortisol spike → action → cortisol drops → recovery.

With chronic stress:

stress → cortisol spike → another stressor → another one →

cortisol never really comes back down.

Under this constant stress:

the cortisol receptors in the brain become less sensitive,

the brain “sees” the elevated cortisol less and keeps pushing production,

allostatic load increases: the system is overworked, the energy bill explodes.

Typical consequences:

Non-restorative sleep Cortisol still high in the evening → blocks melatonin → less deep sleep. Even after 8 hours in bed, you don’t feel restored.

Unstable blood sugar Cortisol stimulates sugar production by the liver. Result: blood glucose climbs even when fasting, insulin has to work harder, cravings increase.

Low-grade inflammation When cortisol is high all the time, it loses its anti-inflammatory effect. Background inflammation rises, impacting the heart, blood vessels and pain.

“Depleted” hormone reserves Cortisol, DHEA, testosterone and oestrogens are made from the same basic building blocks. When cortisol demand is chronic, the body prioritises survival (cortisol) over hormones that support vitality.

In real life: you’re not “just stressed” → you’re chemically depleted in hormones that support libido, motivation, exercise capacity and emotional stability.

When everything feels “too much”, it’s not a willpower issue:

it’s often a sign your allostatic load is too high and the system needs support.

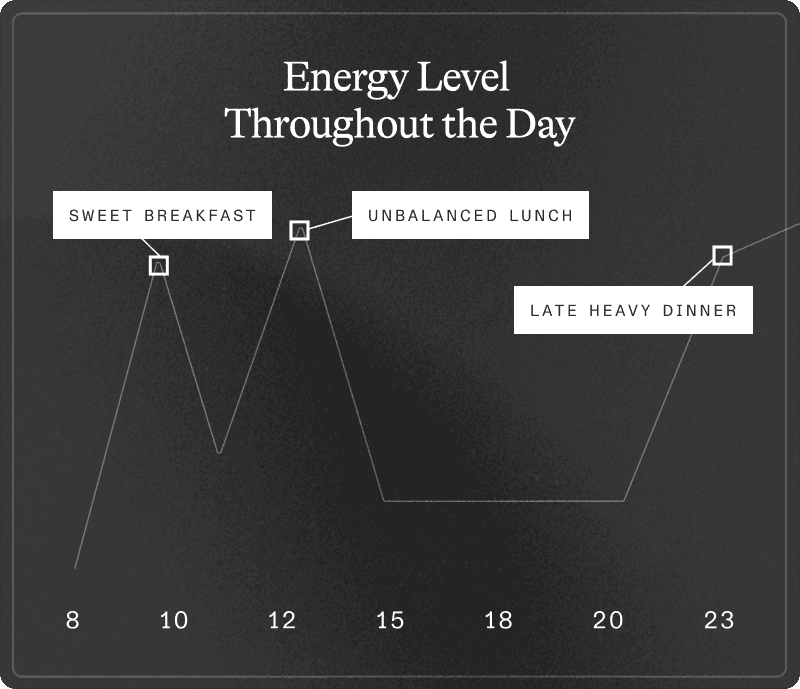

2. Blood sugar rollercoaster: when energy crashes

Between sweet breakfasts, biscuits and alcohol, your blood sugar is on a rollercoaster.

A word on carbs (and why they’re not all the same)

Simple carbohydrates: sugar, juice, sodas, pastries, white bread, sweets, alcohol… → very fast rise in blood sugar.

Complex carbohydrates rich in fibre:lentils, chickpeas, whole grains, sweet potato, quinoa… → fibre slows absorption, → the rise is more gradual, therefore less costly for the system.

What exhausts your body isn’t “carbs” in general:

it’s the repeated spikes without protein, without fibre, on a system already under stress (high cortisol).

The explosive duo: cortisol + glucose

When you combine:

high cortisol (stress, lack of sleep),

repeated sugar spikes,

you create a traffic jam in your “energy factories”.

Result:

lots of sugar in the blood,

but energy that still crashes.

You feel it as:

huge energy dips,

brain fog,

needing coffee + sugar just to function.

Reactive hypoglycaemia: the crash after the spike

The vicious cycle:

Sugar spike (pastry, chocolates, alcohol on an empty stomach)

Strong insulin response

Rapid drop in sugar → reactive hypoglycaemia

Fatigue, irritability, urgent need for sugar

New spike → loop repeats.

Consequences:

higher risk of insulin resistance,

storage of visceral fat (especially around the abdomen),

chronic inflammation,

night-time awakenings (sugar drop around 2–4 am → cortisol + adrenaline surge → waking up).

If your energy feels like a rollercoaster, there’s often a metabolic message behind it.

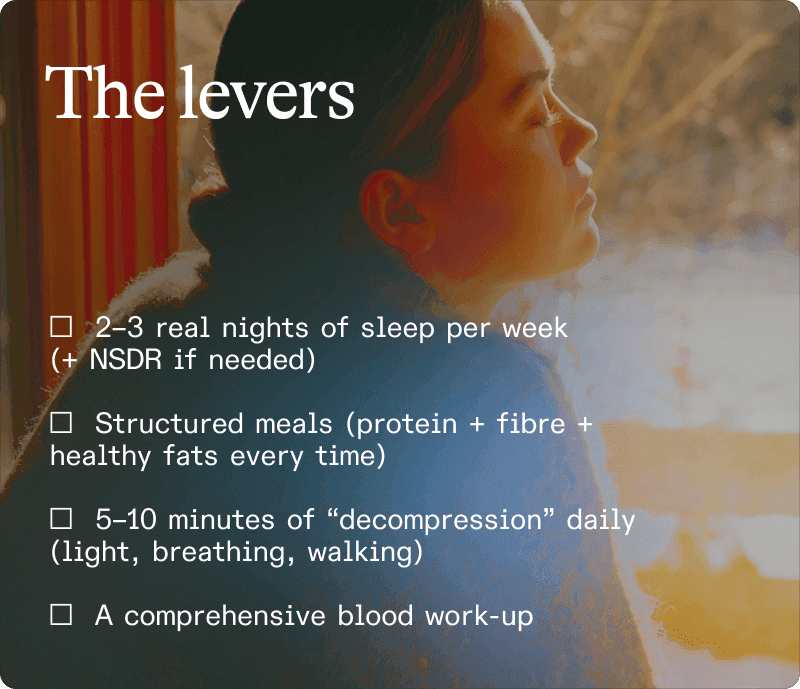

3 habits to reduce allostatic load now

No need to overhaul your life in the middle of December.

Just a few habits that directly reduce the energy bill.

1. Protect a few real nights of repair

You can’t control everything, but you can protect 2–3 evenings per week:

no late events or screens,

a consistent bedtime,

no alcohol (it fragments deep sleep),

a cool, dark bedroom (18–19°C).

When 7 hours of sleep are not realistic, add 10–20 minutes of NSDR / Yoga Nidra (guided audio) during the day:

lowers stress system activation,

helps the body “downshift” even if nights aren’t perfect.

Think of it as a short nap for your nervous system, even if you don’t actually fall asleep.

2. Structure meals to reduce the rollercoaster

Goal: enjoy the same celebrations, with a lower cost for your energy.

Basics:

Always pair carbs with protein + fats + fibre: more stable energy curve.

Avoid fast sugars on their own (juice, alcohol, pastries, biscuits on an empty stomach).

Keep the treats for the end of the meal: start with vegetables + protein + healthy fats → then starches → then dessert / chocolate. → sugar spike is lower, energy bill is smaller.

3. Bring stress down every day (5–10 minutes is enough)

Three simple micro-rituals:

Morning light exposure (10–15 minutes within an hour of waking) → helps reset your internal clock, and with it your cortisol / melatonin rhythm.

Structured breathing in the evening (3–5 minutes) → double inhale through the nose → long exhale through the mouth → activates the vagus nerve → clear message to the body: “you can switch off now”.

Short walk after a meal (10–15 minutes) → helps muscles take up glucose, → reduces blood sugar spikes, → unloads the stress system.

4. Making your allostatic load visible

If you want to go beyond “how you feel”, a Lucis blood panel allows you to map out your allostatic load:

cortisol profile (stress response),

DHEA-S (resilience reserve),

blood sugar markers,

low-grade inflammation (hsCRP).

The idea is to move from

“I’m exhausted and I don’t know why”

to

“I can see where my system is compensating and how I can actually support it”.

References

Gerritsen RJS, Band GPH. (2018). Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Front Hum Neurosci. 12:397.

Kjaer TW, et al. (2002). Increased dopamine tone during meditation-induced change of consciousness. Cogn Brain Res. 13(2):255-259.

McEwen BS, Stellar E. (1993). Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med. 153(18):2093-101.

McEwen BS. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 87(3):873-904.

Montgomery MK, Turner N. (2015). Mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance: an update. Endocr Connect. 4(1):R1-R15.

Picard M, McEwen BS. (2018). Psychological Stress and Mitochondria: A Systematic Review. Psychosom Med. 80(2):141-153.

Ridker PM. (2003). Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation. 107(3):363-369.

Shukla AP, et al. (2019). Food Order Has a Significant Impact on Postprandial Glucose and Insulin Levels. Diabetes Care. 38(7):e98-e99.

Van Cauter E, et al. (2008). Impact of sleep and sleep loss on neuroendocrine and metabolic function. Horm Res. 67(Suppl 1):2-9.

Weickert MO, Pfeiffer AF. (2008). Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes. J Nutr. 138(3):439-442.