In this article

What really happens when you sleepSleep phases and deep sleepThe 4 Dimensions of truly restorative sleepWhat disrupts deep sleep1. Chronic stress: when cortisol stays elevated2. Unstable blood sugar3. Inappropriate body temperature4. Light, stimulation, and circadian disruptionThe vicious circleNatural aidsTracking your progressThe essential takeaway🎙️ Going further: special fatigue episode with Dr. Pauline JumeauSCIENTIFIC REFERENCESIn this article

What really happens when you sleepSleep phases and deep sleepThe 4 Dimensions of truly restorative sleepWhat disrupts deep sleep1. Chronic stress: when cortisol stays elevated2. Unstable blood sugar3. Inappropriate body temperature4. Light, stimulation, and circadian disruptionThe vicious circleNatural aidsTracking your progressThe essential takeaway🎙️ Going further: special fatigue episode with Dr. Pauline JumeauSCIENTIFIC REFERENCES

Why 8 hours of sleep isn't enough and keys habits for deep sleep

Why Sleep Doesn’t Always Equal RecoveryFebruary 4, 2026The holiday season is coming, you imagine sleeping 10 hours... but even after long nights, you don't feel rested. The problem isn't always quantity but the quality of your sleep and more specifically deep sleep.

What really happens when you sleep

We often hear "sleep 8 hours" but rarely talk about what matters just as much: your sleep structure, your cycles, and whether you go through the right phases, in the right order, long enough.

Sleep phases and deep sleep

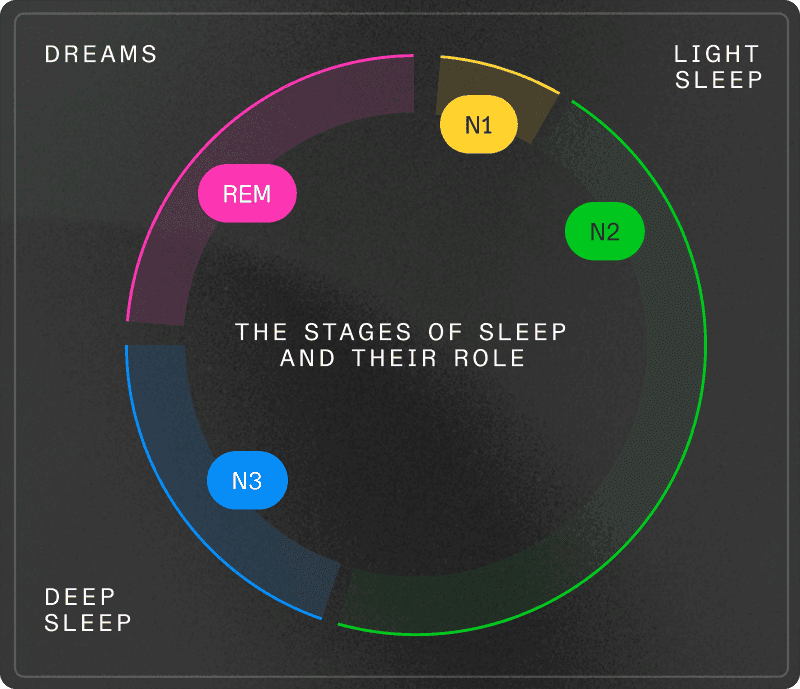

Each night, you go through several sleep cycles of about 90 minutes, composed of 4 distinct phases:

Light sleep (50% of the night): transition phase where your heart rate slows and your temperature drops.

Deep sleep (15-25% of the night): this is the physical repair phase that's often lacking. It represents about 1 to 2 hours per night, concentrated in the first half. During this phase:

95% of growth hormone is produced (muscle repair, tissue regeneration)

The glymphatic system removes brain toxins (beta-amyloid, tau protein associated with Alzheimer's)

The immune system strengthens through cytokine production

Memories consolidate

REM sleep (20-25% of the night): phase of emotional processing and learning consolidation, mostly in the second half of the night.

The key point: going to bed late, even if you sleep long afterward, makes you miss this optimal window in the first 3-4 hours.

The 4 Dimensions of truly restorative sleep

Beyond deep sleep, four factors determine whether your sleep is truly restorative:

Quantity: 7 to 9 hours to cover enough complete cycles including deep sleep (physical repair) and REM (emotional processing).

Quality: sleep continuity. Sleeping 8 fragmented hours interrupted by micro-awakenings doesn't equal 8 hours in one block. Your brain can't access deep phases if you're regularly pulled to the surface.

Regularity: going to bed at roughly the same time each day (±30 minutes) anchors your internal clock. Drastically shifting your schedule creates "social jet lag." Studies show that sleep regularity is a better predictor of longevity than duration alone.

Timing: alignment with your natural chronotype. Sleeping outside your biological hours decreases sleep quality.

If your sleep is fragmented, you don't go through the stages that repair your body. That's why you can sleep long enough and wake up feeling like nothing recharged. Because biologically, nothing recharged.

What disrupts deep sleep

Even if you spend 8 hours in bed, several biological mechanisms can prevent you from accessing deep sleep.

1. Chronic stress: when cortisol stays elevated

Normally, cortisol follows a precise rhythm: peak in the morning, gradual decline, low level in the evening to make room for melatonin.

In chronic stress, this rhythm becomes dysregulated. Cortisol stays elevated late in the evening and blocks melatonin production.

Result: difficulty falling asleep, lighter sleep, less time in deep sleep.

This is the allostatic load mechanism: when your stress system is constantly activated, it depletes your reserves and disrupts your hormonal rhythms, including sleep.

→ The solution: reset your circadian clock

Your circadian rhythm orchestrates cortisol and melatonin. Resetting it via natural light is the most powerful lever.

In the morning (within an hour of waking):

Go outside for 10 to 15 minutes of natural light exposure, ideally before 10am.

Even on cloudy days, outdoor light is 10 to 100 times more intense than indoor lighting.

Late afternoon:

See the sunset or go outside for 10-15 minutes in late afternoon. This anchors the day/night transition.

After 8pm:

Dim the lights. Favor low lamps rather than overhead lighting.

If you must use screens, lower brightness to minimum and activate night mode.

2. Unstable blood sugar

Your blood sugar directly influences your sleep through two mechanisms:

The sharp rise: after a meal rich in simple carbs (sugar, alcohol, refined starches), your blood sugar spikes rapidly. Your pancreas releases lots of insulin. Sometimes too much. You then fall into reactive hypoglycemia.

The nighttime drop: if your blood sugar drops too low during the night, your body secretes cortisol and adrenaline to raise sugar levels. These alert hormones pull you out of deep sleep.

Consequences: nighttime awakenings (especially between 2-4am), fragmented sleep, fatigue upon waking despite sufficient hours in bed.

The case of alcohol: alcohol helps you fall asleep quickly (sedative effect), but it fragments your sleep by multiplying micro-awakenings and blocking access to deep sleep.

→ The solution: stabilize your blood sugar

Meal timing:

Last meal 2 to 3 hours before bedtime.

If hungry later, favor a small snack rich in protein and fats (nuts, Greek yogurt).

Evening meal composition:

Protein + fiber + good fats: they slow carb absorption and avoid spikes.

Favor complex carbs: quinoa, legumes, sweet potato, whole grains.

Limit isolated simple carbs: sweet desserts, white bread, white pasta, fruit juice.

If you have dessert, have it at the end of the meal: fiber and protein consumed before buffer the glucose rise.

Sleep-promoting foods: Kiwis, cherries (natural melatonin), fatty fish (omega-3, magnesium), chamomile infusions.

3. Inappropriate body temperature

To enter deep sleep, your body must lower its core temperature by about 1 to 2°C through peripheral vasodilation: your hands and feet warm up (releasing heat), your core cools down.

If your room is too warm (> 20°C/68°F), your body can't achieve this thermal descent. You stay in lighter sleep.

→ The solution: create the physiological conditions

Room temperature:

Aim for 18-19°C (64-66°F). If impossible, open a window or use a fan.

Stick your hands or feet out of the covers to facilitate heat release.

Heat before bed (counter-intuitive but effective):

Take a hot bath or shower 1 to 2 hours before bedtime.

Heat dilates your peripheral vessels. The post-bath cooling triggers drowsiness.

4. Light, stimulation, and circadian disruption

Your internal clock is calibrated by light. Specialized retinal cells detect light and signal your brain to suppress melatonin (bright light in evening) or produce it (darkness).

The evening light problem:

Exposure to intense light after 8pm (screens, LEDs, overhead lights) suppresses melatonin and delays your clock. You miss the optimal deep sleep window.

Beyond light, screens add stimulation: news, social media, intense series keep your brain on alert. This activates your sympathetic system (action) and prevents the transition to parasympathetic (rest).

The importance of regularity:

Irregular schedules desynchronize your internal clock. "Social jet lag" (late on weekends, early on weekdays) has the same effects as time zone changes: chronic fatigue, fragmented sleep.

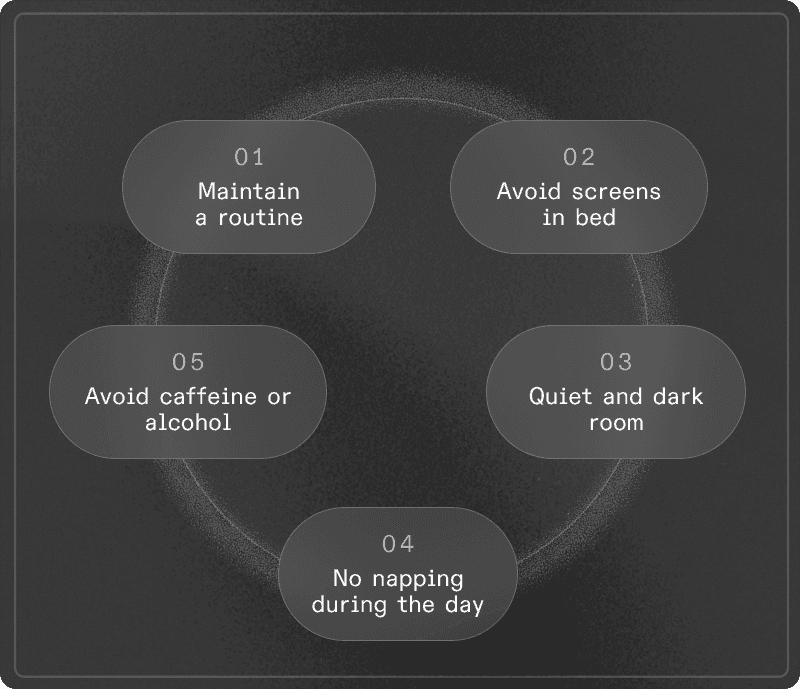

→ The solution: establish a transition routine

Your nervous system needs 30-60 minutes of "deceleration" to shift from alert mode to rest mode.

Create a fixed ritual (same order, same duration, each evening):

Yoga Nidra / NSDR: 10-20 minutes of guided audio (free on YouTube)

Paper reading: avoid stimulating subjects (thrillers, news)

Structured breathing: long exhalations (inhale 4s, exhale 8s, 5 min)

Brain dump: write down what's on your mind and tomorrow's tasks on paper

Avoid: intense screens, activating conversations, work or problem-solving.

The vicious circle

These 4 factors feed each other:

Stress elevates cortisol → disrupts blood sugar → causes nighttime awakenings → increases stress → late light delays sleep onset → you sleep less → lack of deep sleep weakens your immunity and stress management capacity.

When you don't sleep deeply, multiple systems are under pressure simultaneously.

Natural aids

Optional, to use with caution

Some nutrients can support sleep mechanisms if you have deficiencies. Any supplementation should be discussed with a healthcare professional.

Magnesium (threonate/glycinate): promotes GABA, muscle relaxation, sleep onsetGlycine: lowers core body temperature, improves subjective sleep qualityTheanine: relaxation without sedation (caution: may intensify dreams)Melatonin: resets the clock for jet lag. Effective doses: 0.3-1 mg. Avoid in young people.

Tracking your progress

With tracker: deep sleep 15-25% (1-2h), efficiency ≥ 85%, regularity ± 30 minWithout tracker: natural awakening, alert in 15-30 min, no afternoon crash, no compulsive caffeine need

What Lucis can measure:

If your efforts don't yield results, it may be useful to measure your cortisol profile, DHEA-S, inflammation markers (hsCRP), fasting glucose and HbA1c to see where the system is failing and build a protocol adapted to your biology.

The essential takeaway

The holiday season is an opportunity to reset your sleep by establishing habits you can then maintain, even partially, in daily life.

You don't need to do everything perfectly. Even 2 or 3 of these rituals, applied regularly, can transform your deep sleep quality and by extension, your energy, mental clarity, and stress management capacity.

Sleep isn't a luxury. It's the foundation on which everything else is built.

🎙️ Going further: special fatigue episode with Dr. Pauline Jumeau

If you feel like you're doing everything right for your sleep but still remain exhausted several days a week, this episode is for you.

With Dr. Pauline Jumeau, PharmD specialized in biohacking & functional health, we go beyond "sleep more": we discuss blood sugar, stress axis, thyroid, digestion, deficiencies... and how these systems sabotage (or support) your energy.

👉 Listen to the episode: https://youtu.be/k9oXtoJn-cY?si=FlEdDRzcQtNS7Iwy

SCIENTIFIC REFERENCES

Carskadon, M.A., Dement, W.C. (2011). Monitoring and staging human sleep. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Elsevier Saunders.

Berson, D.M., Dunn, F.A., Takao, M. (2002). Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science, 295(5557), 1070-1073.

Chang, A.M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J.F., Czeisler, C.A. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep. PNAS, 112(4), 1232-1237.

Ebrahim, I.O., Shapiro, C.M., Williams, A.J., Fenwick, P.B. (2013). Alcohol and sleep I: effects on normal sleep. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(4), 539-549.

Irwin, M.R. (2015). Why sleep is important for health. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 143-172.

McEwen, B.S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873-904.

Okamoto-Mizuno, K., Mizuno, K. (2012). Effects of thermal environment on sleep. Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 31(1), 14.

Van Cauter, E., Spiegel, K., Tasali, E., Leproult, R. (2008). Metabolic consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Medicine, 9(Suppl 1), S23-S28.

Van Cauter, E., Plat, L., Copinschi, G. (1998). Interrelations between sleep and the somatotropic axis. Sleep, 21(6), 553-566.

Xie, L., Kang, H., Xu, Q., et al. (2013). Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science, 342(6156), 373-377.